“Low-tech Magazine questions the belief in technological progress, and highlights the potential of past knowledge and technologies for designing a sustainable society” (Kris de Decker, “About the Solar Powered Website”). To reduce energy use, the website applies basic web design, default typefaces, dithered images, off-line reading options, and other tricks. “In addition, the low resource requirements and open design help to keep the blog accessible for visitors with older computers and/or less reliable Internet connections. It needs 1 to 2.5 watts of power, which is supplied by a small, off-grid solar PV system on the balcony of the author’s home. This means that the website will go off-line during longer periods of cloudy weather” (Kris de Decker, “About the Solar Powered Website”).

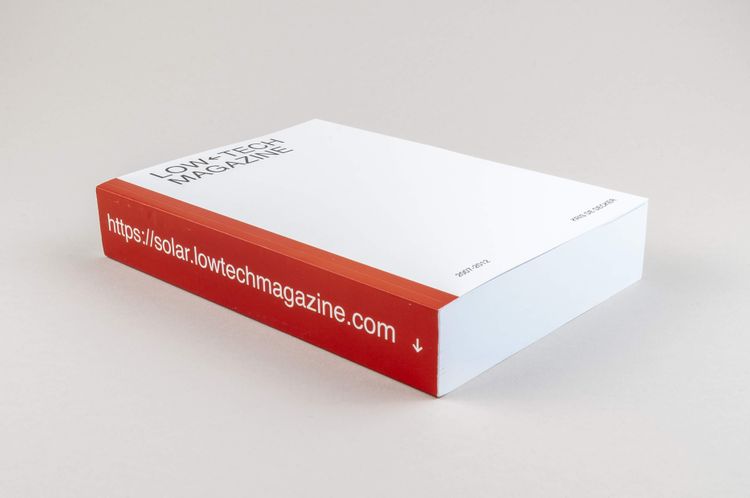

To be able to read Low-tech Magazine without access to a computer, a power supply, or the internet, and also to preserve content in the longer term, Low-tech Magazine has been made available in paper form since 2019. The printed archives now amount to four volumes with a total of 2,398 pages, covering the blog posts as well their comments from 2007 to 2021. Further volumes are planned, once every one to three years. Readers are encouraged to send in additional comments, which will be included in the next edition: “Our printer allows books of up to 800 pages, so there is room for further debate” (Kris de Decker, “The Printed Comments”). However, the volume with the comments is legally in a gray area, because it was impossible to determine their actual authors: “The truth is that nobody really knows who wrote this book. It’s a work of the commons” (Kris de Decker, “The Printed Comments”).

Print-on-demand was chosen for environmental reasons: “there are no unsold copies (and no large upfront investment costs). Our US publisher Lulu.com works with printers all over the world, so that most copies are produced locally and travel relatively short distances. […] Lulu prints on FSC-certified, acid-free paper” (Kris de Decker, “The Printed Website”).

The “printed website” was designed by Lauren Traugott-Campbell. “For the book, the hyperlinks have been converted to references, and dead links have been replaced by links to copies of pages recorded by the Internet Archive. Ironically, the references in the book are now more up-to-date than those on the website” (Kris de Decker, “Second Volume Out Now”).

One year after the launch, more than 2,000 copies have been sold worldwide. After receiving a batch of poorly printed and bound copies, de Decker added a post on dealing with such loss of quality—thus skilling his readers in quality control when print-on-demand platforms outsource this procedure to the buyer (Kris de Decker, “How to recognize a badly printed Lulu book”).

In 2021, a second edition of the second volume was published: “This new edition has almost twice as many images and follows the same design as the other volumes. In contrast to the first edition, the images are not ‘dithered’ and of higher quality. We use a smaller font to pack more content on fewer pages. This second edition also fixes some errors in the articles and the references” (Kris de Decker, “Volume III & The Comments”).