Olivier Bertrand has made the production of books in margins the basic principle of his publishing house Surfaces Utiles. Bertrand characterizes his publishing strategy with the French expression “faire la perruque,” borrowed from Michel de Certeau and describing a kind of détournement: what is meant by this is using the working time and the working means, resources, or tools of a company to one’s own advantage, or to the company’s disadvantage.

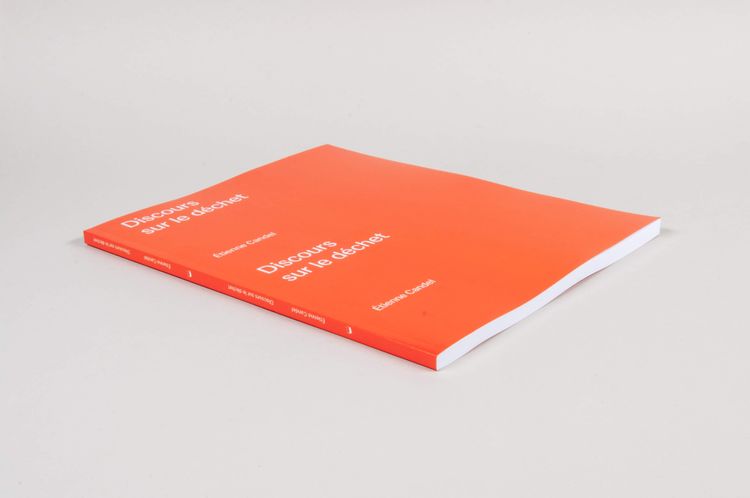

In this book from his publishing house Surfaces Utiles, the publisher and designer Olivier Bertrand once again applies his subversive publishing strategy of “faire la perruque.” The imprint openly declares the second, revised and expanded edition of Étienne Candel’s Discours sur le déchet to be a “détournement des services d’une plateforme d’impression à la demande” (hijacking the services of a print-on-demand platform).

Again, it is Blurb whose cheapest standard format becomes the raw material for the production of the actual book: Two copies of the final product can be produced from each Blurb print. On the strip that remains is Blurb’s ISBN, which Bertrand cuts off so he can print his own publisher’s mark on the books. These leftover strips are like mini bound books themselves, which the artist sometimes gives away and sometimes uses as a notebook.

Etienne Candel’s “trashtexts,” which he usually presents on his Instagram account, fit perfectly into this publication strategy: The artist tracks down abandoned bulky waste on the street and—in keeping with the name of Bertrand’s publishing house—describes its “useful surfaces” with sometimes witty, sometimes philosophical, sometimes sociocritical sayings tailored to the object or the found situation, which he then signs with the tag “&c.” and photographs: “The ‘Speech on Waste’ [...] proposes changing our way of seeing the discarded, the obsolete and the residual. Printed on the precious paperscraps of Surfaces Utiles, this book also illustrates the manifesto of a publishing house that publishes by virtue of what the industry sheds as ‘waste’” (publisher website, blurb).

An index at the end of the book sorts the situational photos with their sayings into equally dazzling categories such as “farniente” (idleness) and “gueules cassées” (broken jaws). Under the latter heading, for example, is a discarded folding chair that seems to sigh, “Holy Sit [sic].” Some sayings gain their punchline from the clash of different languages, like the waste bin labeled “Ich bin” (I am) indexed under the heading “philosophie de comptoir” (bar stool philosophers). The result is “a bulky-waste prosopopoeia [...] coming straight out of the toothless mouths that populate the city. It is an entire fauna of marginal people leaned up on Haussmanian facades, jabbering about and calling out: cat-burglar bandits, seductresses, unemployed professionals or nostalgic retirees, bar stool philosophers and failed artists, tramps united in solidarity and post party hangovers, etc.” (publisher website, blurb).

For the first edition, Bertrand used leftovers of 10 × 100 cm, which dictated the format of the book to be produced. However, the printing proved to be quite difficult, as the presses regularly stopped working because it was not a DIN format. In the end, only sixty copies could be produced instead of hundred, and the edition was sold out very quickly. Bertrand lacked the appropriate paper for a second edition, so he switched to Blurb, as he had done with What’s Left Over From the Works of Le Bon.